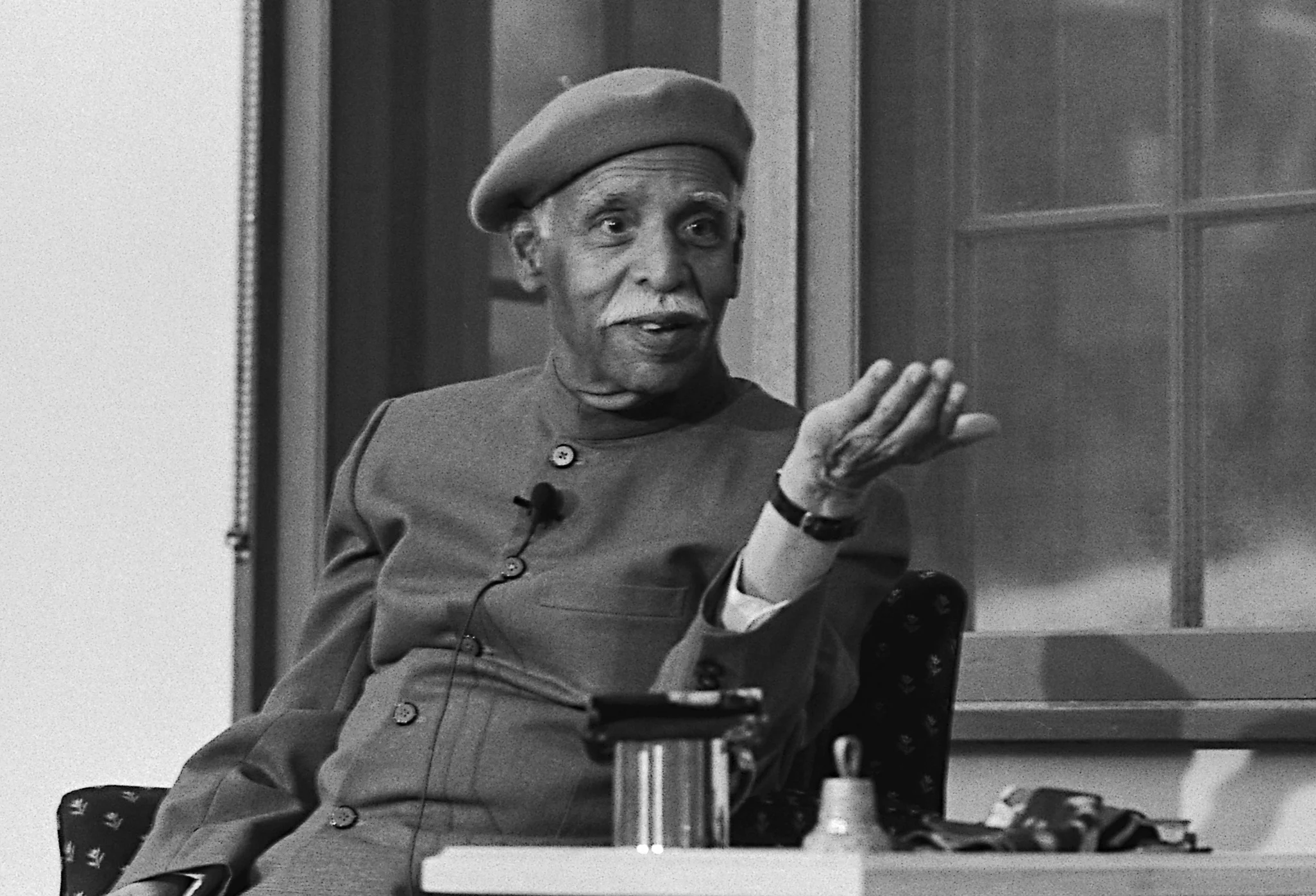

Eknath Easwaran: All of Us Are One

/This week we bring you an excerpt by Eknath Easwaran from the Blue Mountain Journal.

The same spark of divinity - this same Self - is enshrined in every creature. My real Self is not different from yours nor anyone else's. The mystics are telling us that if we want to live in the joy that increases with time, if we want to live in true freedom independent of circumstances, then we must strive to realize that even if there are four people in our family or forty at our place of work, there is only one Self.

This realization enables us to learn to conduct ourselves with respect to everyone around us, even if they provoke us or dislike us or say unkind things about us. And that increasing respect will make us more and more secure. It will enable us gradually to win everybody's respect, even those who disagree with us or seem disagreeable.

When these sages talk about “realization,” what they mean is making this Self a reality in our daily living. We have to practice it in our behavior. Never talk ill of others, they are saying, even if they have faults; it doesn't help them and it doesn't help you. Always focus on the bright side of the other person: it helps them and it helps you. Work together in harmony even if you have serious differences; it will rub the angles and corners off your own personality. Then you will never feel lonely, you will never feel deserted, you will never feel inadequate; you will be unshakably secure. Interestingly enough, this gradually makes those around us more secure too.

The Upanishads tell us these words should “enter the ear.” They shouldn't just beat about the lobes; they should go in – and not just in through one ear and come out the other; we should let their wisdom sink into the mind. Then, the Upanishads say, “Reflect on them”: learn to practice these teachings in your daily life.

When we see people who are difficult to work with, for example, that's the time to practice. Instead of avoiding such people or quarreling with them, why not try to work with them? Why not work in harmony and try to support them?

This doesn't mean conniving at weaknesses, and it doesn't mean we have to say yes to everything they do or say; that’s a wrong conception. To connive at somebody who is not living up to his responsibilities not only doesn't help the situation; it doesn't help that person either. Seeing the Self in those around us means supporting them to do better – again, not through words, but through unvarying respect and personal example. It is this unwavering focus on the Self in others that helps them realize its presence in themselves – and in us and others as well.

Focusing on the Self in all

Because all of us are one, most personal problems and weaknesses are really very similar. As the Upanishad says, they differ “only in name and form.” Almost everyone is subject to insecurity, even those who appear most forceful; getting angry and throwing one’s weight around are signs of insecurity, not strength. Similarly, most of us are subject to dwelling on ourselves, often with negative feelings that can be terribly oppressive. In such cases anyone can feel inadequate, unable to cope with the responsibilities of the day.

Similarly, all of us have times when we are patient, days when we are kind, because beneath our passing, everyday personality, this transcendent Self is always present. It does people great harm to forget this and give them the impression that they are nogood by focusing attention on their faults.

Spiritual living means learning to do just the opposite. Whatever a person’s problems, we can learn to keep our attention always on the divinity within. After a while they start thinking, “Well, she must see something in me that I have never seen. Maybe it’s really there.” And slowly they begin to act on this belief.

Thérèse of Lisieux, a charming and very gifted saint of nineteenth-century France who died in her early twenties, was a great artist at this. In her convent there was a senior nun whose manner Thérèse found offensive in every way. Like many of her sister nuns, I imagine, all that she wanted was to avoid this unfortunate woman. But Thérèse had daring. Where everyone else would slip away, she began to go out of her way to see this woman who made her skin crawl. She would speak kindly to her, sometimes bring her flowers, give her her best smile, and in general “do everything for her that I would do for someone I most love.” Because of this unwavering love, the woman began to feel more secure and to respond to Thérèse’s attentions.

One day, in one of the most memorable scenes in Thérèse’s autobiography, this other nun goes to Thérèse and asks, “Tell me, Sister, what is it about me that you find so appealing? You have such love in your smile when you see me, and your eyes shine with happiness.”

“Oh!” Thérèse writes. “How could I tell her that it was Jesus I loved in her – Jesus who makes sweet that which is most bitter.”

Sometimes people tell me, “I can’t pretend like that! It’s hypocritical.” But Thérèse was not pretending. That divine spark at the core of personality is more real than anything else. In relating to Jesus in that sister rather than to her moods and caprices, she was relating to her real Self – and, by her constancy, actually bringing it to life.

Ninety-Nine Percent the Same

It is relatively easy to see the Self in others when they agree with us. It becomes difficult when they criticize us or do the opposite of what we want. But contrariness is part of life. We come from different homes, went to different schools, have been exposed to different influences, hold different views; it is only natural that we differ in all kinds of ways. Yet these differences amount to no more than one percent of who we are. Ninety-nine percent is what we have in common. When we see only that one percent of difference, life can be terribly difficult. When we put our attention on the Self in others, however, we cease dwelling on ourselves, and that opens our awareness to the much larger whole in which all of us are the same, with the same fears, the same desires, the same hopes, the same human foibles. Then, instead of separating us, the one percent of superficial differences that remains makes up the drama of life.

I remember a song from Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers: “You like tomayto and I like tomahto; let’s call the whole thing off.” That is all most differences amount to. If you can keep your eyes on what we have in common, you will find that most differences cease to bother you. You can remember that the other person has feelings which are just as easily hurt as yours. He too appreciates it when other people are kind – he is ninety-nine percent you. She too appreciates it when you are patient, even if she herself is irritating – she is ninety-nine percent you.

Being with people who are different is not only unavoidable; it is necessary if we want to grow. Without the company of those who differ from us, we grow rigid and narrow-minded. Those who associate only with people their own age, for example, lose a great deal: the young have much to learn from the old, and older people from the young. Similarly, if you are a blue-collar worker, it is good to know an intellectual or two; it will cure you of any awe you might have of higher education. Even the difference between an egghead and a hardhat is only one percent. Their feelings, their responses to life’s perennial problems, are very much the same.

Most of us can treat others with respect under certain circumstances – at the right time, with the right people, in a certain place. When those circumstances are absent, we usually move away. We avoid someone, change jobs, leave home, move to southern California. Yet when we respond according to how the other person behaves, changing whenever she changes, and she is behaving in this same way, how can we expect anything but insecurity on both sides? There is nothing solid to build on.

Instead, we can learn to respond always to the Self within – focusing not on the other person’s ups and downs, likes and dislikes, but always on what is changeless in each of us. Then others grow to trust us. They know they can count on us – and that makes us more secure too.

We can try to remember this always: the same Self that makes us worthy of respect and love is present equally in everyone around us. When we base our relationships on this unity, showing unwavering respect and unconditional love to all, we give them – and ourselves – a sure basis on which to stand. Everyone responds to this. It is one of the surest ways I know of to make our latent divinity a reality in daily life.